ARLINGTON — What began as a simple rearrangement of the lounge’s decor led members of American Legion Post 76 to discover a 71-year-old piece of history that had been sitting under their noses for decades.

David Delancy and Randy Harper were handling an artillery shell that had been part of a small memorial in the lounge, intending to secure it more firmly to the floor. When they opened it up they discovered the shell casing was nowhere near as empty as they’d thought.

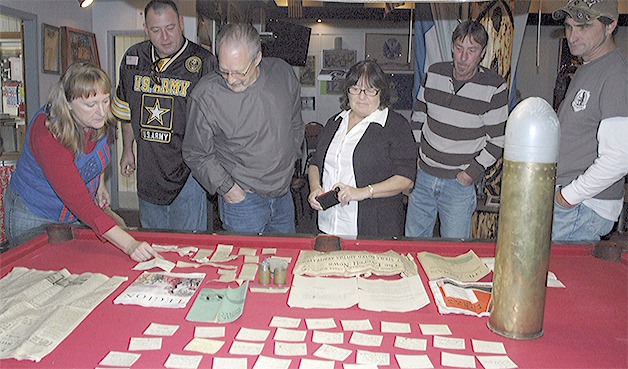

The shell head was a wooden replica, and the casing had been turned into a time capsule containing documents and artifacts from 1934.

Inside were front pages from The Everett News and The Everett Daily Herald, a menu from the Monte Cristo Hotel in Everett, a World War I trench-lighter, an Indian head nickel, and copies of the military publications Legion Monthly, The Indian and The Forty And Eighter.

“For the longest time, I don’t even know how long, it was just sitting in our curio case,” Delancy said. “We had no idea what it was. It’s been opened at least once before, though, since we found a note saying, ‘Thank you for the brandy.’”

Several clipped and yellowed newspaper articles from 1934 had been placed in Ziploc plastic bags, also indicating the time capsule’s contents had been discovered by a previous party.

Although none of the Arlington Legion members can remember when or even how they acquired the artillery shell, it included a typed letter, on stationery with the Everett Clinic as its letterhead, addressed “to the two survivors of the Last Man’s Club.”

An enclosed list of names, addresses and phone numbers for the club indicates that it had 42 members at the time, including H.R. Secoy, who instructed that his letter should be delivered to either his older son, Clyde Frank Secoy, or his younger son, Harry Raymond Secoy, depending on which one was still alive.

The elder Secoy also requested that those who read his words should pass on “the best wishes of the writer” to the Everett Clinic, if it “still be in existence.”

Delancy’s wife, Dorine, has contacted her doctor, Scott Schaff, who serves on the Everett Clinic’s board of directors, to see if the clinic might have any luck in contacting either Secoy’s sons or any surviving members of the Last Man’s Club.

“We tried to look them up, but we couldn’t find any of them,” Delancy said. “We’re taking our time to figure out the history here.”

In the meantime, the Legion is discussing what to do with the time capsule and its contents.

“Do we just put it all back?” Delancy asked. “Do we add artifacts of our own to it? If so, what do we include?”

Harper added: “We’ve talked about storing music and photos on memory sticks, but depending on how data storage technology progresses in the future, I’m afraid of future generations opening it all up and saying, ‘So what the heck are we supposed to do with these things?’”

Delancy conceded it’s likely that hard copies of any new documents will be included, in addition to digital data, just to be on the safe side.

He laughed as he added that fellow Legion member Ray Klosterhoff was born July 21, 1934, three days after the date on Secoy’s letter.

“Back when he wrote that letter, the youngest member of that club was thirty-three years old, born in 1901,” Delancy said, referring to a note signed by L.B. “Bud” Hatch. “Just about everyone else had been born in the 1800s. That really puts that era into perspective.”